Passover comes this Sunday, a rite from the Biblical story of Exodus, wherein the enslaved Israelites win their freedom from Pharaoh. It seems a fitting context for a discussion of The Acres, an indentured ecosystem on the wildland-urban interface.

Passover comes this Sunday, a rite from the Biblical story of Exodus, wherein the enslaved Israelites win their freedom from Pharaoh. It seems a fitting context for a discussion of The Acres, an indentured ecosystem on the wildland-urban interface.

These substantial and privately-held native grasslands rise between the town of Brisbane and the state and county park of San Bruno Mountain. A walk here is like a page from the California history book -- steep hoary stands of melic and fescue athwart canyons of buckeye and oak, and vast savannahs of butterfly sage punctuated by johnny jump-up, silver lupine, and broadleaf stonecrop, the larval food plants of rare and endangered butterflies.

Carved into jigsaw-puzzle pieces by an "unrecorded subdivision" (i.e. illegally) in the 1930s, with titles now held by hundreds of individuals, The Acres live in a state of bondage. Houses already cover twenty of the original 111 parcels (all on the lower slopes), and developers have mapped routes for possible roads and building envelopes throughout the remaining 120 wild acres. Opinions among owners radically diverge: some would like to preserve their land as open space, while others want to build. One fellow proposed turning his one-acre parcel into an Indian casino. Where is Moses when you need him?

The near-horizontal pitch of these slide-prone grades would appear to discourage your average builder -- but the Bay Area real estate market is anything but average. Already the narrow private roads on the lower, comparatively gentle slopes "typically do not meet fire code standards," according to the City of Brisbane. Some of the proposed new streets in the steeps are merely drawn on paper; others follow the mad path of Virgil Karns, an eccentric local landowner from decades ago who joyrode his bulldozer up and down these sheer ridges in his spare time.

Below the water tower, near the intersection of Beatrice and Margaret (two of Virgil's former dozer runs), a footpath splits off from the road. Perhaps an old Indian trail or a current corridor for wildlife, it plunges through poison oak and fords a seasonal stream, then climbs into an old-growth forest of gnarled oak, dwarfed madrone, fruiting toyon, ocean spray, and blooming Ceanothus. The sounds of the city grow faint beneath the epic silence of these woods as they stood centuries ago; the intervening years fall away, and suddenly there were no years. Welcome to California circa 1700.

Below the water tower, near the intersection of Beatrice and Margaret (two of Virgil's former dozer runs), a footpath splits off from the road. Perhaps an old Indian trail or a current corridor for wildlife, it plunges through poison oak and fords a seasonal stream, then climbs into an old-growth forest of gnarled oak, dwarfed madrone, fruiting toyon, ocean spray, and blooming Ceanothus. The sounds of the city grow faint beneath the epic silence of these woods as they stood centuries ago; the intervening years fall away, and suddenly there were no years. Welcome to California circa 1700.

The once and former Eastwood manzanita (Arctostaphylos glandulosa) stretches its red serpentine branches for the light that pushes through openings in the canopy. This tree-like shrub grows to 6-8 feet tall and grows from a large basal burl, from which it will readily resprout after fire. Specimens so regenerated can live for hundreds of years. But flames have not touched this landscape within memory, and the manzanitas look tired. They crave a good burn.

After another switchback the path rises into grassland, where the rare and endangered Diablo Helianthella (Helianthella castenea) waves its golden sunflower blossoms and the aromatic hummingbird sage (Salvia spathacea) grows in five-thousand-square-foot savannahs. Thick 3-foot clumps of California fescue (Festuca californica) hold the hill, while the silvery inflorescence of melic grass (Melica californica) dances with the purple owl's clover (Castilleja exserta), goldfields (Lasthenia californica), and many other spring wildflowers. In a quick informal survey, I counted 50 species.

Wherever the trail passes an exposed slab of greywacke, the slate-colored foundation stone of the mountain, look for the broadleaf stonecrop (Sedum spathulifolium), a spreading succulent clinging to cracks in the rock. Each exquisite rosette of slightly reddish green pushes up thumb-sized flower stalks, whose yellow inflorescence shines against the greyish stone. This plant feeds the caterpillars of the Bay Area endemic and federally protected San Bruno elfin butterfly. Home gardeners and commercial landscapers, take note -- it also makes a wonderful accent in any exposed stone hardscaping, and a handsome addition to the rock garden.

Noteworthy among the many other standouts this month is the coast larkspur (Delphinium decorum ssp. decorum), a gorgeous dark-blue flower with a nodding 2-foot habit and a prominent spur. The Mendocino Indians prized larkspur for its narcotic properties, but please note this genus contains toxic alkaloids that have killed cattle, so no "experimentation" is advised.

Glorious in bloom, these lands and their many animal inhabitants lie in limbo. Will it require the plague of locusts, thundershower of frogs, and death of the firstborn of Egypt to liberate these natives from private ownership? Who among ye will daub the blood of the lamb on their doorposts?

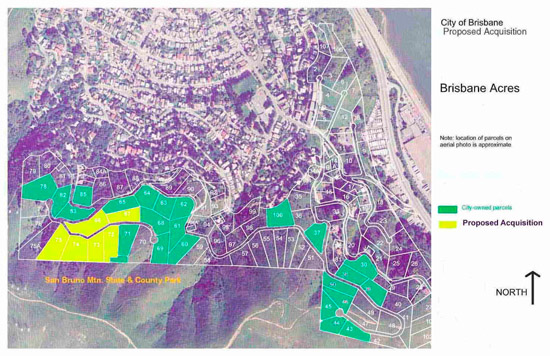

We Will, answered the city of Brisbane. Heeding calls from citizens who value the wilderness over the subdivision, the city began buying parcels of The Acres in 1997, using money set aside annually for open space acquisitions and with grants from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and the California Coastal Commission. This on-going program has stewarded 23 parcels (with six more currently in escrow) covering more than 30 acres into city-owned open space, including one contiguous block of the canyons and grasslands southwest of the water tower and another in the prime butterfly habitat of the upper Bayshore Ridge. This is good cause for rejoicing.

Nonetheless, dangers remain. Some would like to build a dream house here, capitalizing on that million-dollar view of San Francisco. Rampant populations of blue gum Eucalyptus, broom, fennel, and other weeds escape from residential areas into untrammeled zones; these degrade the native diversity and kill off local species. Brisbane's vegetation management plan spends $20,000 annually to combat exotic invasives, with the optimistic goal of total eradication.

But native plants also invade -- coastal scrub, for example, encroaches into grassland when not checked by fire. Fred Smith, assistant to the Brisbane city manager, named "succession to scrub" alongside development and weeds as the top three threats facing The Acres today.

The book of Exodus gives explicit instructions for Passover, including the preparation and consumption of the sacrificial lamb. "You shall let none of it remain until the morning," warns the Lord. "Anything that remains until the morning you shall burn."

More easily said than done. A controlled burn two summers ago in Wax Myrtle Canyon, for example, jumped its planned 5-acre boundary and spread to 75, ending up a stone's throw from residential housing. Judged by the rejuvenated landscape, this project was a tremendous success -- but the risk to human settlements raised some eyebrows.

Such are the paradoxes along the wildland-urban interface. Proceed at your own risk and reward.

* * *

Geoffrey Coffey is a member of the tribe, a freelance writer for the San Francisco Chronicle, and the founder of Madroño landscape design studio. He gives thanks to David Schooley of San Bruno Mountain Watch for the guided tour of Brisbane Acres.