“I just hiked to the top of Cedar Mountain Ridge,” wrote Pete Veilleux, proprietor of East Bay Wilds landscaping, “and found some very cool plants including a bigberry manzanita 40 feet tall!”

Incredulity rippled through the native plant coven. The standing record for any manzanita was 32 feet, according to Tilden Park Botanical Gardens local expert Bert Johnson. A 40-foot manzanita has never been recorded. Veilleux explained that he hadn’t measured exactly, but only eyeballed the height; Johnson urged him to return as soon as possible with a yardstick or a tape measure. Tempted by the thrill of the chase, I joined Veilleux and Paul Furman, landscape architect and photographer, to revisit the mountain and measure the monster manzanita.

Cedar Mountain Ridge rises near Livermore in southeastern Alameda County between the Crane and Rocky Ridges, a veritable wonderland of rare and unusual plant communities. It’s 20 miles up Arroyo Mocho to this enchanted region, mostly private property off-limits to the public. Veilleux discovered the manzanita in a remote canyon above the Los Mochos boy scout camp. “I would never trespass,” he said, then elaborated with a grin: “I try not to get caught.”

I phoned the boy scout camp three times requesting permission for an informal botanizing expedition. My calls were not returned.

We parked on the side of Mines Road, hopped the fence onto boy scout land, and walked uphill along the creek. No scouting activities are scheduled for the rainy season, and the camp was utterly deserted. Veilleux and Furman, both knowledgeable plantsmen, called out with great relish the names of the native species we encountered. It was a step back in time to an era before highways and Hollywood, before gold miners and agriculture, before mankind ever assumed ownership of the earth.

“Look! Ribes speciosum!” called Veilleux, using the Latin name for the fuchsia-flowered gooseberry.

“Here’s Rhamnus tomentella!” answered Furman, fingering the velvety twigs of the hoary coffeeberry.

Their excitement was catching, and I marveled at our lush surroundings. Clumps of robust oniongrass (Mellica imperfecta) and California fescue (Festuca californica) anchored swaths of creeping red fescue (F. rubra) and bluegrass (Poa secunda). Groves of white oak (Quercus lobata) stood unclothed, their deeply lobed leaves now shed like a dark carpet upon the wet land. In the creek, dense bunches of naked sedge (Carex nudata) painted the landscape an orange-tinted green while another unidentified sedge glowed an exquisite shade of blue. Blue-grey tufts of saltgrass (Disctichlis spicata) blanketed the mineral-encrusted soil beside a seep, and vigorous stands of the uncommon Hamilton thistle (Cirsium fontinale var. campylon) clung to rocky embankments.

Furman scrutinized some small grasses bunched on a serpentine outcrop. “What’s this, Calamagrostis?”

“Looks suspicious,” replied Veilleux.

“No,” insisted Furman, “it looks like something good!”

Fellow native plant enthusiasts (or “plant geeks,” as Furman calls us) understand this dichotomy between the original plant species and the exotic invasives that displace them: populations of the former are multifaceted and historic, while relentless waves of the latter push us all toward an impoverished monoculture. Even the casual hiker not versed in the finer points of floristic taxonomy would appreciate the rich feeling of Cedar Mountain Ridge, where the diversity is deep enough to baffle a botanist.

We crested a rise and crossed an open meadow past a wooden water tank sentried by a dilapidated double-wide trailer (for sale, according to a sign in the window). Following a short path, we skirted a silent rifle range and climbed into heavy chaparral. This deep scrub has not burned in perhaps 75 years, leaving it in a late stage of its ecological life cycle: thick old branches and lots of deadwood unregenerated by fire. We pulled on our work gloves and crashed through the undergrowth as best we could.

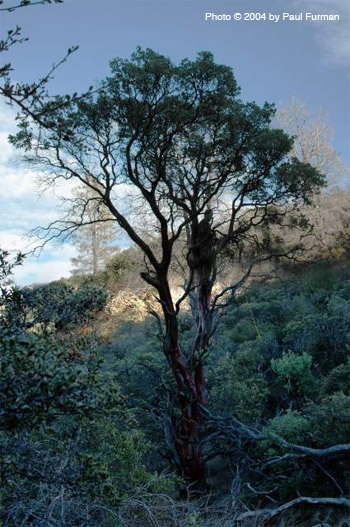

Here the bigberry manzanita (Arctostaphylos glauca) grows in dense association with silk tassels (Garrya congdonii) and the leather oak (Quercus durata). As we plowed through the interlocked branches, often on our hands and knees, we noticed that most of the manzanitas were the same height — 8 to 10 feet tall — meaning they were all the same age, a forest germinated from seed after a single burn. The deep red, twisted branches of Arctostaphylos glauca look particularly attractive against the luminous grey-green foliage, the delicate white bloom in late December, and the oversized berries of the mature fruit.

Occupying the middle zone of our tango with the tangle, Garrya congdonii grows 4-5 feet tall with a squat “silk tassel” bloom in January. It’s related to the taller and more attractive G. elliptica or coastal silk tassel, which produces the long elegant flowers prized by horticulture and enjoyed by astute gardeners during the bleak rainy months.

The low-growing leather oaks impeded our way the most: these 3-foot evergreen shrubs with the stout furry twigs and elephant-hide leaves are tough and impassable. It seemed a surreal inversion to have oaks growing low and scrubby beneath us while manzanitas reached for the sky!

All three plants (and especially the leather oaks) are serpentine indicators, and indeed the “elfin forest” character of this winter-blooming landscape derives from the poor nutrient and high toxin content of the serpentine soil, in which only the most highly adapted plants can survive. All these plants would have grown at least 50% taller in regular edaphic conditions, but also would have faced wider competition from a multitude of other species.

Nearing the top of the canyon, we began to see scattered pine and more Sargent cypress (Cupressus sargentii), the conifer with the cedar-like scent for which the ridge was named. This gorgeous tree has blue needles when young but turns a dark green with age; it grows quickly to 10 feet tall and then slowly thereafter, approximately 1 foot per year, to 50 feet.

Suddenly, as we turned into a north-south chasm on the edge of the ridge, our goal appeared above the tangle: the top of a towering manzanita, the giant Arctostaphylos glauca, our holy grail.

The tree rose from a single stem, rare for this species, then split into two branches at about the 8 foot point. The gnarled trunk measured 76 inches in circumference at breast height, twice as thick as a man’s torso.

I gave Veilleux a foothold with my hands and pushed him up into the crotch of the tree. He climbed the leading branch and used a tape measure to calculate the distance from top to bottom: 33 feet! Though shy of the 40 he originally estimated, this still marks the new world record for any species of the genus Arctostaphylos.

We rested for a few minutes to bask in historic glory, then pushed on for the jeep trail at the top of the ridge, our turning point for home. Atop the summit we spied the distant snowy peaks of the Sierra shimmering like watchful gods across the central valley, and all the mountains conspired to embrace us with a simple but arcane knowledge. The earth does not belong to us; we belong to the earth.

* * *

Geoffrey Coffey left his boy scout troop at age 12 in favor of playing the piano. He is the founder of Madroño landscape design studio and a freelance writer for the San Francisco Chronicle.

Madroño president Geoffrey Coffey started the company in 2005 out of the back of a pickup truck. His garden column, “Locals Only”, first appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle in 2002. He lives in San Francisco with his wife and two children, where he also sings and thumps the bass for Rare Device.