Few explorers would expect to find a beach hidden in the middle of a redwood grove. Yet such incongruities lurk in the mountains above Santa Cruz, where ancient seabeds upthrust millions of years ago by tectonic turmoil gave rise to stark hills of sand now tucked among lush evergreen forests more than five miles from the sea. Fossilized sand dollars and shark teeth in the ground testify to the marine origin of these Santa Cruz sandhills, whose so-called Zayante soils support a rare and unusual community of native plants found no place else on earth.

The Bonny Doon Ecological Preserve is the largest and most accessible of these unique habitats, with 550 acres and a network of trails open to the public during daylight hours. Walking these paths of heavy sand, one expects to hear the roar of the surf around every corner — yet the ear meets nothing but the sound of a mountain breeze whispering through the surrounding woods.

Here we find a dominant population of the rare and endangered Bonny Doon manzanita (Arctostaphylos silvicola), an upright shrub from 5-15 feet tall with gorgeous silver foliage and a gnarled trunk of deep red vein-like branches. Sunlight shining at an angle through the leaves can cause this foliage to glow as if from within, rendering the landscape otherworldly and magical.

Just now the manzanitas are bursting into bloom with clusters of delicate white urn-shaped flowers, attracting squadrons of hungry hummingbirds. The Bonny Doon manzanita is endemic to the Santa Cruz sandhills and does not occur anywhere else on the planet; but it has been taken into cultivation and is (very occasionally) available through the horticultural trade. For its distinctive evergreen foliage, bright winter blossoms, and striking architectural habit, the taller species of Arctostaphylos make an excellent choice as focal points in the native plant garden — and the Bonny Doon manzanita stands among the most arrestingly beautiful of them all.

Bonny Doon contains several other endangered species that grow here and only here. The annual Ben Lomond spineflower (Chorizanthe pungens var. hartwegiana), for example, covers wide swaths of the sand with a bright pink bloom every spring, its small white flowers surrounded by spiny pink bracts that give this plant both its common name and its underlying color. Another rare spring bloomer is the Santa Cruz wallflower (Erysimum teretifolium), a biennial that grows a silvery basal rosette of needle-like leaves its first year, blooms a brilliant yellow in its second spring, then dries up and dies, leaving behind only a seed bank as the foundation for next year’s growth.

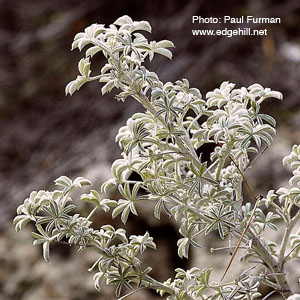

Silvery color characterizes the leaves of many other members of the Bonny Doon flora, an adaptation that reflects sunlight and thus helps these plants conserve precious water in such dry and unforgiving conditions. Take the Ben Lomond wild buckwheat (Eriogonum nudum var. decurrens), another rare and endangered species, with delicate white hairs on its spoon-shaped leaves and a summer bloom of tiny white flowers held in dense heads like cotton balls. Wild buckwheats draw many native bees and other beneficial insects to feed on their flowers, which in turn attract a host of native birds to feed on the bugs; home gardeners seeking to attract wildlife, take note. While the Ben Lomond buckwheat is protected and not cultivated for the trade, Eriogonum is the largest dicot genus in California with approximately 250 species, many of which are available to home gardeners and are analogous wildlife magnets. Here in the Bay Area, ask your nurseryman for E. latifolium, our most common local variety, or E. ‘grande rubescens,’ a beautiful red-blooming selection from San Miguel Island.

Scattered widely throughout Bonny Doon’s sandy open areas, the silver lupine (Lupinus albifrons var. albifrons) and the silvery-white fragrant everlasting (Gnaphalium canescens ssp. beneolens) yield further evidence of the prevailing color scheme. This species of lupine is common in chaparral and foothill woodlands throughout California, where it can grow to a shrub of 6 feet and closer to green in color, but here in the sandhills it stays lower and more compact (no more than 2 feet tall), its tight leaves with a shiny hue like a bright new coin. The fragrant everlasting rises like a white lock of wool to a height of 2 feet, its leaves linear in basal tufts with an aroma like minty pineapple; deployed in the garden or planned landscape, everlasting can be useful as edging along paths or to define the boundaries of a planted flower bed.

Isolated ecosystems like Bonny Doon serve as Darwinistic laboratories, where plants have evolved into micro-populations genetically distinct from their more widespread cousins. This may explain the number of silver-leafed endemic species restricted to such a narrow range, and also the several “undescribed species” like the tipless tidy tips (Layia platyglossa), the slender gilia (Gilia tenuiflora), and the Zayante everlasting (Gnaphalium sp. nov.) that demonstrate evolution in progress and warrant further taxonomic research. But the Santa Cruz sandhills also host several disjunct populations of plants that normally grow elsewhere — closer to the ocean, for example, in the obvious case of mock heather (Ericameria ericoides), sea pink (Armeria maritima var. californica), and beach sagewort (Artemisia pycnocephala). It does stand to reason that such beach-loving species would thrive here in the sandy soils of an ancient seabed, but we may still wonder how they came to dwell here on a mountain so far from the shore. More perplexing is the presence of Ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa), a common tree in the Sierra above 3,000 feet but rather unusual this far west. Local botanist and revegetation specialist Valerie Haley explains that these pines were once considered their own distinct species, Pinus benthamiana, but later were lumped together with Pinus ponderosa — although other botanists still argue whether or not to put them in their own subspecies. “These pines have 7 or 8 features that are different from those in the Sierra,” says Haley, “but that’s not always enough to convince the taxonomists.”

Unbowed by the indignities of modern nomenclature, the flora of Bonny Doon exudes its own proud charisma, with a cool zeitgeist that endows this region with the sense of a silvery paradise regained. Local residents have pitched in with a volunteer program, organized by Haley, that meets once a month to clear trails, pick up litter, and otherwise support the underfunded and overworked Dept. of Fish & Game in maintaining the beauty of this rare and endangered preserve. Such relationships underscore the dividends generated by like-minded people who rally around the common goal of deepening our connections to earth. Whether at the beach, in the redwood forest, or some enchanted zone in between, native plants (and the people who cultivate them) help to define our special identity of place.

* * *

Geoffrey Coffey propagates the Bonny Doon manzanita for Bay Natives nursery. He is the founder of Madroño landscape design studio and a freelance writer for the San Francisco Chronicle.

Madroño president Geoffrey Coffey started the company in 2005 out of the back of a pickup truck. His garden column, “Locals Only”, first appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle in 2002. He lives in San Francisco with his wife and two children, where he also sings and thumps the bass for Rare Device.