Mysterious and epic dramas take place at the bottom of the sea, where massive forces meet microbiology. In the red peaks of Corona Heights we can read an engrossing chapter: this stark hill with the distinctive flora and the unbeatable view over San Francisco is composed of the fossilized shells of prehistoric sea creatures. Formerly quarried for bricks, the site today hosts the Randall Children’s Museum, a coterie of dog walkers, and a remarkably strong community of California native plants.

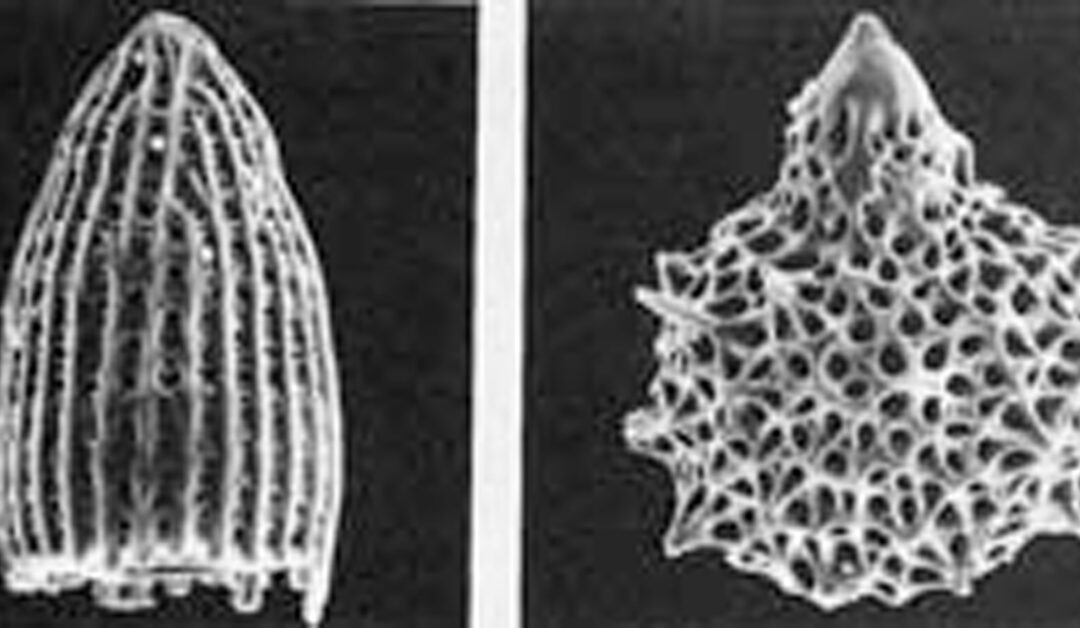

The back-story: single-celled organisms ruled the Ocean Deep during the Cambrian period, some 500 million years ago. Radiolaria, the most prolific of these protozoa, grew microscopic silica shells of fantastic and unlikely beauty, often spherical or helmet-shaped with delicate spines radiating from the center, in thousands of distinct variations; they dominated the primordial brine for over 300 million years, and still survive in diminished numbers today. As their spent shells sank over eons in what Silent Spring author Rachel Carson calls “the long snowfall,” countless layers of fine sediment accumulated into a thick coat of radiolarian ooze on the ocean floor. Time and pressure turned it to stone.

Flinty chert, the rock used by native peoples to make arrowheads and knives, is in fact this same petrified radiolarian ooze disrupted by plate tectonics and lifted to the surface. It forms San Francisco’s system of radiolarian peaks, that scimitar of red chert cutting through the city: Lone Mountain, the camel humps of Buena Vista and Corona Heights, Sunset Heights, Twin Peaks, Mt. Davidson, the San Miguel Hills, Bernal Heights, and Bayview Hill.

Witness the raw power of the ages in the striated rock of Corona Heights — particularly the 40-foot cliff face near 15th and Beaver Streets, where the impressive red layers are twisted and warped, testifying not only to hundreds of millions of years of “radiolarian rain” and the crushing weight of the ocean, but also to the unspeakable violence that ripped this stone from its bed in the sea and thrust it into the sky.

Chert makes relatively dry and nutrient-poor soil, so the flora of Corona Heights is distinguished in its ability to thrive under inauspicious growing conditions. Gardeners take note: plants native to this area can survive cultivation under the most negligent or otherwise unlucky of brown thumbs. Constant coyote bush (Baccharis pilularis) and plucky wild buckwheat (Eriogonum spp.) prosper here, as in other inhospitable California habitats, supporting a precious population of local birds and butterflies; wind-resistant and drought-tolerant, they make proud and enduring elements in any California habitat garden. More colorful is the sticky monkeyflower (Mimulus aurantiacus), a hardy perennial whose golden orange blossoms dot the rocky upper slopes of Corona Heights throughout the summer. Horticulturalists breed monkeyflower hybrids in varieties of white, red, yellow, and other hues, guaranteeing a shade to match any gardener’s color scheme.

Wildflowers play a colorful role on the botanical stage, and the lupines of Corona Heights put on a remarkable show. Lupinus bicolor grows to around 1 foot tall with velvet palmate leaves and a terrific blue and white bloom, while the flowers of L. variicolor, a silky prostrate perennial, range from blue and white to purple, pinkish, and yellow. They make a nice foil for the persistent pink blossoms of the low-growing Sidalcea malveflora, whose leaves come in two different shapes: larger and rounder at the base of the plant, smaller and more deeply lobed near the top. Growing together in the garden as in nature, sidalcea and lupine complement each other with reciprocal shapes, colors, and textures.

The western morning glory (Convolvulus occidentalis) also holds court at Corona Heights, with twining vine-like stems growing around stony outcroppings and over adjacent shrubs; the flower is white to pinkish, with a funnel-shaped corolla unfurling from a twisted bud. In the garden, morning glories work well on slopes and in tandem with shrubs and small trees, through the branches of which they may climb.

Further, Corona Heights hosts two unusual color variations: the lemon yellow California Poppy and the white Blue Dick. The former, Eschscholtzia californica var. maritima, occurs naturally in coastal environments. The latter, Dichelostemma capitatum, is usually blue (as the common name implies), but the white form haunts the chert grasslands of San Francisco’s incongruous radiolarian peaks like the fluttering spirits of those long-departed microscopic sea monsters.

* * *

Geoffrey Coffey is the founder of Madrono landscape design studio, a principal of Bay Natives nursery, and a freelance writer for the San Francisco Chronicle.

Madroño president Geoffrey Coffey started the company in 2005 out of the back of a pickup truck. His garden column, “Locals Only”, first appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle in 2002. He lives in San Francisco with his wife and two children, where he also sings and thumps the bass for Rare Device.